by Maisie Tomlinson

This essay accompanies a dramaturgical piece featured in Edition 14 of So Fi Zine

Read the full edition here.

“Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth”, declared the novelist Albert Camus. The inclusion of this aphorism, in a recent presentation to an interdisciplinary animal research conference, provoked some audience discomfort. After all, fictional representations of animal laboratories are rarely “kitchen sink” dramas. From The Island of Dr Moreau to Guardians of the Galaxy 3, these are more often experiments in wild, exaggerated monstrosity, complete with mad professors and raging human-animal hybrids. It was argued that animal rights protestors often drew on similarly dramatic, misleading fictions to demonise researchers. What responsibility, one attendee asked, did artists have towards accuracy, realism and “truth” in representations of laboratory life? Here, I take up this question, from my perspective as a sociologist and sometime theatre-maker, whose play What a Mouse Knows, inspired by research with laboratory animal welfare professionals, was written and produced two years ago (Tomlinson, 2023).

The play draws on findings from my ethnographic investigation into the practice of “critical anthropomorphism” in animal behaviour studies (Tomlinson, 2021). My findings echoed studies that have shown, time and again, that the practice of science is never a simple matter of detached objectivism, but is inextricable from what Maria Puig de la Bellacasca (2011) calls the “matters of care” that hold it together. Matters of care might include, for example, the labour involved to maintain scientific equipment, or the emotional histories and ethical commitments that forge a research interest. It incorporates the time, imagination and social exchanges needed to speculate on connections and methodologies. Research findings, she argues, are fundamentally constituted by such matters.

In this vein, the lives of laboratory animal welfare professionals are often characterised by very particular “matters of care”. They inhabit a strange paradox: typically drawn to the profession out of affection for animals, they often find themselves inflicting pain and suffering on them in order to study, and ideally prevent it. They work within a science that has been historically marginalised and remains, at times, othered by “human-benefit” research colleagues, wary of the limitations that animal welfare measures impose on their work. At yet, that commitment to animal welfare does not protect from the same stigma around their place of employment that those colleagues often experience. In particular, my own participants also described the epistemological challenges of working with mice. Despite significant seniority and experience, several professionals described mice as uniquely, frustratingly unpredictable, even deceptive. And yet simultaneously, the relative success of their arguments was creating, some told me, an almost untenable pressure to deliver measurable answers to seemingly unanswerable questions about the nature, trajectory, accumulation and proportionality of animal experience. Interview encounters were, therefore, never straightforward accounts of the “facts”, but haunted by interpersonal difficulties, frustrations, regrets, ethical anxieties, and care. This is a far cry not only from the demonic scientists of Hollywood fiction, but also from the highly managed “windows” into animal research offered as part of the Concordat on Openness, where confidence can be taken for granted, and nobody ever cries, doubts, bites, or walks out.

It was one or two such striking moments of revelation that began the journey of What a Mouse Knows, funded by an ESRC postdoctoral fellowship. I hoped to bring alive some of these ethical, emotional, embodied experiences for a public audience. Using drama to explore and/or communicate research findings has been done many times before (see, for example, AnNex, 2019). However, unlike many of these projects, which often work with fragmented scenes, audience participation, or dialogue more faithful to interview encounters, I chose to work in a traditional play format, with a fixed script, a maintained “fourth wall”, and a plotline inspired by, but also distant from, my fieldnotes and transcripts. The relevance of accuracy, realism and “truth”, therefore, can reasonably be questioned.

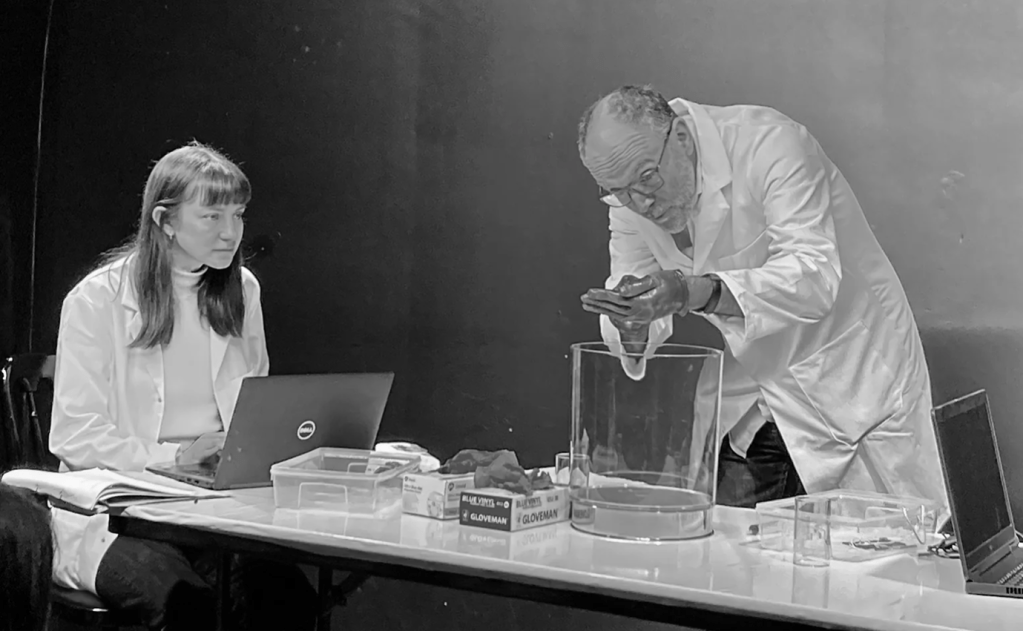

The play centres on a senior animal welfare scientist, Edward, who is assigned to work with his estranged young niece; not seen since his wife, her aunt Jean, committed suicide ten years ago. A forthright and ambitious Annalise is conducting epilepsy research with a single mouse in a metabolic cage, and Edward has been asked to piggy-back his own welfare research off her own. It is a frosty start, and the pair struggle to work with very different understandings of Mouse 476997, how to handle her, and how to understand her behaviour. Annalise’s sudden appearance emotionally disturbs Edward, giving him strange dreams; but their shared love of music, underpinning family memories, draws them into a tentative, uncertain alliance. However, when a dispute over handling methods threatens Annalise’s results, unresolved tensions spill into a dramatic confrontation over Jean’s death. When the following morning Mouse 476997 starts behaving inexplicably, Edward is triggered into an increasingly unethical series of experiments to find out why. This leads to his professional downfall, but also a surprising new invention.

The mouse plays a central role, gaining a name (Angel), and increasing powers of agency, and although she is invisible, her presence is indicated through the response of the actors to her behaviour, and the miming of her presence in their hands. For example, in the extract below, Edward asks Annalise to undertake a more qualitative assessment (cf Wemelsfelder, 2001), to overcome her fear of the mouse:

And so rather than a faithful account of a typical working day, uncertain assessments, strange dreams, Greek mythology, uncanny resemblances, inexplicable behaviours, the intrusion of the past into the present, and the ability of music to capture experience are all elements of the play, with a plotline entirely distinct from real events. This doesn’t, however, necessarily make it less ‘real’. As the sociologist Howard Becker writes, with any form of representation, from a scientific report to a photograph, “there is no general answer to: is it true?” There are only “more or less believable” answers to many possible questions, depending on who is asking and for what purpose they are using the representation (2007:112). Moreover, many seemingly contradictory things can be true all at once. In writing the play, I sought to do more justice to some of the more emotional “truths” emerging from my research. Drawing on the evident frustrations of ever truly knowing mouse experience, and the intense creativity needed to try, the play is fundamentally about the limits of knowledge – in science, in human and nonhuman relationships, in grief.

Weaving together a series of authentic transcript extracts might have made for a more faithful account of the data. However, as Rossiter et al (2008) warn, this objective can be challenging to reconcile with the objectives of theatre: to emotionally engage and entertain, and ideally with some artistry. Saldaña warns that those “dramatizing data” must remember that “the ultimate sin of theatre is to bore …” (2003:227). With the kind of interactive, immersive approach taken by some others regrettably outside of my skillset and budget, I believed that complex, rounded characters, an absorbing plotline, and dramatic conflict stood the best chance of drawing an audience into engagement.

It is also true, however, that the framing of the play was dependent on its origins in sociological research. It would be disingenuous to ignore the authoritative currency this carried. Indeed, Becker argues that social realism in art does more than this; it carries an aesthetic force. The belief that a piece of art corresponds to reality can move, shock, outrage or awe (2007:123). Whether this is dishonesty or artistic licence depends, says Becker, on a social agreement borne of the “marks” that a representation displays of its relationship with reality. We expect a different social contract with truth in a statistical table, or in a so-called “documentary”, than we do with a poem. In claiming, then, to be “inspired” by research, there was a responsibility that The Island of Dr Moreau does not have. So, whilst the stakes were deliberately raised to extra-ordinary situations, the details of laboratory life were not. The metabolic cage, for example, gave a realistic justification for a singly-housed mouse. Edward works with real animal welfare indices whose workings the audience can see. Contemporary debates are raised, such as the merits and challenges of tunnel handling, or the impact of mouse captivity on data. Annalise and Edward, one might say, “behave truthfully in imaginary circumstances” (Meisner and Longwell, 1987).

It is this interplay, I believe, of the real and the fictional, that makes many plays, stories, or films so engaging. How successfully What a Mouse Knows accomplishes this is an open question, for others to judge. But in principle, as Mariam Motamedi-Fraser argues, the advantage of playing “make-believe” is that its naked artifice makes an audience both more receptive to, and more active participants in, an experience. “It is difficult”, she argues, “to be in a relation with a preacher who not only tells, but who also often ardently believes in what he is telling” (2012:95).The invitation to accept both doubt and pretence, and make “as if” something were true, engenders, she believes, more creative and critical thinking – an “informed provocation” of experience (ibid), rather than a simple re-telling of it.

So perhaps the successful theatrical representation of animal research depends on a compound of fiction and reality. After all, Iranian stories, Motamedi-Fraser tells us, begin not with “once upon a time” but “one there was, one there wasn’t”. This sense of contradiction is, perhaps, captured in the words of my gatekeeper who kindly checked the script for its scientific accuracy. Despite the protagonist being a grouchy, complex eccentric, who does several awful things, Howard told me: “I read this, and I felt, I know Edward. I don’t mean I know who you have based him on, but know who he is, I can see myself in him”. It was a rewarding exemplar of Camus’ complex interrelation between “lie” and “truth”.

Bibliography

AnNex Animal Research Nexus (2019). Vector. Available at: https://web-archive.southampton.ac.uk/animalresearchnexus.org/events/vector.html (Accessed: 17 December 2024)

Becker, H.S. (2007). Telling About Society. University Of Chicago Press.

Meisner, S., & Longwell, D. (1987). Sanford Meisner on acting. Random House.

Motamedi Fraser, M. (2012). ‘Once upon a Problem’. The Sociological Review, 60(1), 84–107.

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2011). ‘Matters of care in technoscience: assembling neglected things’, Social Studies of Science, 41(1), pp. 85-106.

Rossiter, K., Kontos, P., Colantonio, A., Gilbert, J., Gray, J. and Keightley, M. (2008). Staging data: Theatre as a tool for analysis and knowledge transfer in health research. Social Science & Medicine, 66(1), pp.130–146.

Saldaña, J. (2003) ‘Dramatizing data: a primer’, Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), pp. 218–236.

Tomlinson, M. (2021) ‘“Critical Anthropomorphism” and Multi-Species Ethnography: An Investigation of Animal Behaviour Expertise.’ Research Explorer The University of Manchester. Available at: https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/critical-anthropomorphism-and-multi-species-ethnography-an-invest. (Accessed: 22 May 23).

Tomlinson, M. (2023). ‘What a Mouse Knows: A Play”. So Fi Zine, 14, 9-25. https://sofizine.com/latest-edition/edition-14/

Wemelsfelder, F. (2001). ‘The inside outside aspects of consciousness: complementary approaches to the study of animal emotion’, Animal Welfare, 10, pp. 129-139.